Hey everyone, it’s already been two months since the last blog post!

Today I’m back to share some behind-the-scenes about the struggles and development of a new functionality for Sniffnet: process identification, a.k.a. the most requested feature since the very beginning of the project.

What’s process identification?

With “process identification” in a network monitoring context, I mean the possibility to discover which application or program is responsible for a given network connection.

This can be determined by looking at the open TCP/UDP ports on the system and finding out which process is currently using them.

If implementing this feature seems like a no-brainer to you, well… read on because it turned out to be a much more complex task than I could imagine, and this is the reason why the related GitHub issue has been open for almost 3 years.

Challenges in implementing process identification

First of all, the implementation is highly OS-specific: each platform has its own directories and data structures storing such information, and APIs to interact with them are often not well documented or written in C (therefore not very ergonomic to use from Rust).

And unfortunately, there is no Rust library ready-to-use satisfying the needs of Sniffnet.

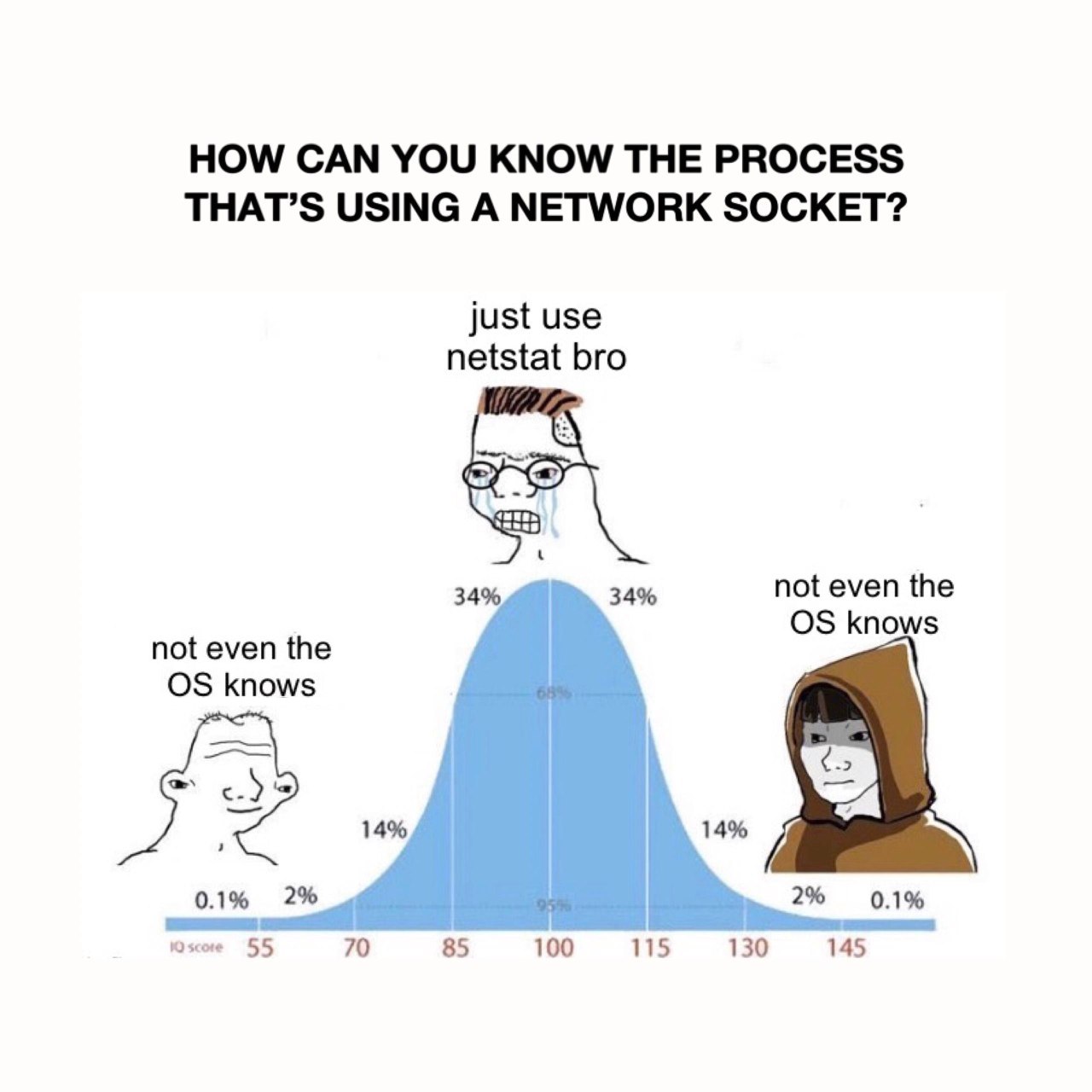

One could argue that this is a solved problem, since there are already existing tools to do it: for instance, on Linux and Windows you have netstat, and on macOS you have lsof or nettop.

However, these tools are not designed to be used as libraries and spawining a shell to execute them repeatedly is not efficient, especially if you want to monitor the network activity in real-time.

Moreover, they don’t provide all the information Sniffnet needs, such as the process name and path.

But the biggest challenge is another one: the least system-intrusive ways to implement the feature are snapshot-based, meaning that they require to read the system state at a given moment in time and do some computations to find out the associations between open ports and their owning processes.

I’m referring to using libproc on macOS, the /proc filesystem on Linux, and iphlpapi on Windows.

This is not a problem in itself, but it generates the need to do this processing very efficiently, and it leads to cases where it’s not possible to retrieve process information at all.

For instance, short-lived connections can go undetected and system processes with elevated privileges can be hidden to user-space applications for security reasons.

More system-intrusive approaches exist, such as using kernel-level hooks to intercept the system calls responsible for creating network connections.

An example of this is eBPF on Linux, which requires to run privileged code inside the kernel.

On macOS, you’d even need entitlements from Apple to be able to do something similar through their Network Extension framework.

While these approaches are way more accurate, they go against Sniffnet’s philosophy of being a lightweight, non-intrusive, and friendly app that can be installed by anyone.

After considering all the options, I decided to go with the snapshot-based approach.

Despite being aware it’s not flawless, I believe it to be the best compromise for Sniffnet’s use case.

The library behind the feature: listeners

listeners is an open-source library I’ve been working on for the past 2 years with the goal of supporting this feature.

Being Sniffnet a cross-platform application, I needed a solution that could work on different Operating Systems: no other Rust crate provides this functionality supporting multiple platforms and the existing ones are not maintained or satisfactory enough even for a single OS.

Interestingly, I also had this same need at my job, where we also wanted a Rust way to do it: this motivated me even further to contribute to the library.

After two years, I’m happy to see that listeners was downloaded 150k times and has now multiple public dependents both on crates.io and GitHub, which means that this is a problem shared among many people.

Just some days ago listeners v0.4.0 was published.

I’m particularly proud of this release for at least two reasons:

- Support for FreeBSD was introduced thanks to my colleague Anton (in addition to the already existing support for Windows, Linux, and macOS).

To my knowledge there is no existing crate at all that does something similar targeting FreeBSD and this is an added value for the library, even if at the moment we’re using Rust-to-C bindings for this.

Huge props to Anton for his contribution, and for having also started adding support for OpenBSD and NetBSD exactly in these hours. - I’ve spent the past week’s nights testing and extensively benchmarking the library, considerably improving the APIs performance.

I had so much fun usingcriterionto benchmark it under different system loads, and I’ve made the results generation completely automated on GitHub Actions runners for all the supported platforms.

You can find the results and more charts in the README’s Benchmarks section.

Thanks to point 2, I now judge the library mature, fast, and reliable enough for use in Sniffnet.

If you’re a Rust developer, you’re more than welcome to contribute to the library trying to make it even faster, or adding support for more Operating Systems (Android and iOS? Why not!).

How Sniffnet will implement the feature

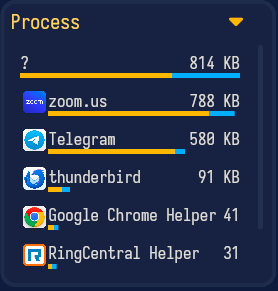

Sniffnet will use listeners to look up the process for each observed network connection, and will show it in the UI’s Overview and Inspect pages.

Additionally, it will use another library called picon (I’m still working on it) to retrieve app icons given their program path, showing them in the UI as well to make it easier to identify processes at a glance.

The workflow I plan to use is indeed pretty complex, including caching to minimize performance impact and retries to maximize the chances to correctly retrieve process information for a given open port.

In the flowchart below I’ve outlined a draft of the strategy I’ll adopt for Sniffnet-side implementation of the feature.

Conclusion

I hope this post wasn’t too scary to read and that it gave you an idea of how much work is behind a seemingly simple feature like this.

Nothing worth having comes easy, someone says.